TROMBOSI DELLA VENA GIUGULARE INTERNA (IJV) E DELLA VENA SUCCLAVIA

Trombosi venosa Giugulare interna e succlavia : un caso di studio e revisione della letteratura

N Jonas, J Fagan

Parole chiave

Trombosi venosa giugulare interna, la sindrome di Lemierre, ascesso polmonare

Citazione

N Jonas, J Fagan giugulare interna trombosi venosa:. Un caso di studio e revisione della letteratura. Internet Journal of Otorinolaringoiatria. 2006 Volume 6 Numero 2.

Riassunto

Trombosi della Vena giugulare (IJV) interna, associata ad infezione suppurativa del tratto aero-digestivo superiore è stata descritta prima un secolo fa. Anche se la reale incidenza di trombosi IJV è sconosciuto sembra essere in aumento. Le complicanze associate con trombosi IJV sono potenzialmente letali ed è quindi importante riconoscere e trattare questa condizione presto. Questo articolo descrive un caso di trombosi infettiva IJV secondaria a media cronica in una bambina di nove anni e una revisione della letteratura.

TROMBOSI DELLA VENA GIUGULARE (IJV) INTERNA IJ E DELLA VENA SUCCLAVIA

Trombosi venosa della Giugulare interna (IJ) si riferisce ad un trombo intraluminale che si verificano ovunque dalla intracranica IJ vena fino al bivio di IJ e della vena succlavia per formare la vena brachiocefalica. Si tratta di una condizione sottodiagnosticata che può verificarsi come complicanza delle infezioni della testa e del collo, nel caso in oggetto di una otite, della chirurgia, l’accesso venoso centrale, malignità locale, policitemia, Iperomocisteinemia, massaggio cervicale, e per via endovenosa (IV) l’abuso di droga. Si segnala inoltre che si verifichi spontaneamente.

Attualmente, con l’uso diffuso della vena IJ per l’accesso venoso, cateteri venosi centrali sono la causa più comune di trombosi IJ. Di preoccupazione è una tendenza che riflette un crescente numero di tossicodipendenti IV che si presentano con IJ trombosi secondaria a ripetute iniezioni di droga direttamente in vena IJ. Altre cause sono tumori maligni locali e la testa, il collo e le procedure chirurgiche cardiache. Cause rare includono policitemia, Iperomocisteinemia e massaggio al collo.

IJ trombosi si può avere gravi complicanze potenzialmente letali, tra cui la sepsi sistemica, chilotorace, papilledema, edema delle vie aeree, e embolia polmonare (EP). Infezione secondaria della trombosi può provocare tromboflebite settica. Un trombo infetto IJ causata da estensione di una infezione orofaringea viene definita come sindrome Lemierre; questo è stato anche definito necrobacillosi o setticemia postanginale.

La diagnosi spesso è molto impegnativo e richiede, in primo luogo, un alto grado di sospetto clinico. L’approccio migliore per fare la diagnosi una volta il sospetto è sollevata non è stata definitivamente stabilita. Uno studio di valutazione per merito comparativo dei tomografia computerizzata (TC), la risonanza magnetica (MRI), e l’ecografia non sarebbe difficile da eseguire.

La morbilità e la mortalità di trombosi venosa IJ sono paragonabili a quelli di estremità superiori trombosi venosa profonda (TVP); di conseguenza, occorre tenere in considerazione per il trattamento di queste due entità in un modo simile.

Studi clinici randomizzati dovrebbero indagare anticoagulante come trattamento primario e superiore collocamento filtro cavale come trattamento secondario nel contesto della terapia anticoagulante che ha fallito o è controindicato. Ad oggi, gli studi clinici non ben progettati hanno effettuato tale indagine. Se, infatti, l’incidenza è alta quanto attualmente sospettata, il problema sarebbe presta ad uno studio randomizzato, studio clinico controllato.

Il trattamento trombolitico è stato raramente utilizzato. Occorre prendere in considerazione per il trattamento di trombosi venosa IJ nella cornice del PE con trombolitici in uno studio clinico randomizzato.

Anatomia

La vena IJ inizia nel cranio a conclusione del seno sigmoideo. Si esce dal cranio attraverso il forame giugulare e poi corsi attraverso il collo anteriore laterale alla carotide, coperte dal muscolo sternocleidomastoideo per la maggior parte della sua lunghezza. Si conclude unendo la vena succlavia, formando così la vena brachiocefalica.

Il processo stiloide divide lo spazio faringeo laterale in una anteriore (muscolare) e un vano compartimento posteriore contenente la carotide all’interno della guaina carotidea, l’IJ vene, nervi cranici IX-XII, e linfonodi.

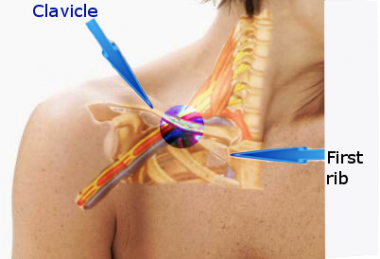

Decorso della vena succlavia sulla prima costola e sulla posteriore alla clavicola; l’arteria si trova superiore e posteriore alla vena (vedi immagine sotto). Sir James Paget primo descrisse la trombosi delle vene succlavia nel 1875. [1] ha coniato il nome flebiti gottoso per descrivere la trombosi spontanea delle vene che drenano l’estremità superiore. Paget ha notato che la sindrome è stata accompagnata da dolore e gonfiore degli arti colpiti, ma ha erroneamente attribuito la sindrome di vasospasmo. Nel 1884, von Schrötter ipotizzato che questa sindrome il risultato di una trombosi occlusiva dei succlavia e ascellari vene. [2] Nel 1949, in riconoscimento del lavoro di questi pionieri, Hughes ha coniato il termine sindrome di Paget-von Schrötter. [3]

Questa figura mostra l’area in cui la vena succlavia è ostruito nella zona del collo. La vena di solito è compressa dalla prima costola, clavicola, e muscolo dentato anteriore.

Argomento di studio

Un bambino di otto-anno-vecchia ragazza ha presentato al nostro ufficio con una lunga storia di sinistra otorrea lato e una storia di cinque giorni di febbre e otalgia. All’esame la temperatura era di 39,8 ° C e il suo orecchio sinistro era pieno di mucopus. L’esame del suo orecchio sinistro ha rivelato una perforazione subtotale della membrana timpanica con nessuna evidenza di colesteatoma. C’era lieve dolorabilità su di lei mastoide senza evidenza di un ascesso mastoide. La sua funzione del nervo facciale era intatto. Un audiogramma ha rivelato una perdita di 60 dB conduttiva dell’udito nell’orecchio sinistro e udito normale nell’orecchio destro.

E ‘stata ricoverata in ospedale e trattati con ampicillina per via endovenosa e metronidazolo. Dopo tre giorni aveva ancora alte temperature persistenti e ha sviluppato un ascesso mastoidea post-auricolare. Una TC è stato eseguito che ha mostrato un osso mastoideo opacizzato e una possibile trombosi del seno sigmoideo. Non c’è stata evidenza di una collezione intra-cranica.

Un mastoidectomy radicale modificata è stata eseguita rivelato che una grande quantità di tessuto di granulazione nell’orecchio medio e mastoide. Il seno sigmoideo è stato esposto e ha rivelato un trombo infetto che è stato evacuato. I campioni sono stati inviati per l’istologia e la cultura.

Nel corso dei cinque giorni ha continuato a picco alte temperature e dolore al collo sviluppato. L’esame ha rivelato un’offerta, cavo di massa simile sul lato sinistro del collo. L’ecografia del collo ha rivelato una trombosi vena giugulare interna sinistra. I campioni inviati in precedenza durante l’intervento chirurgico mastoide in coltura di Pseudomonas sensibile alla Gentamicina e Amikacina. A causa del risultato coltura positiva e trombo vena giugulare abbiamo aggiunto endovenosa amikacina a sua terapia antibiotica.

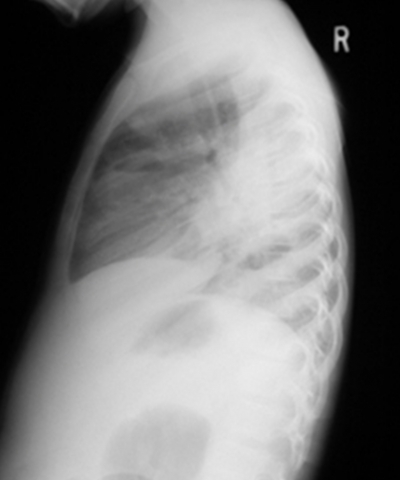

Nei prossimi due giorni la paziente ha continuato a picco alte temperature e sviluppato una tosse produttiva. La radiografia del torace ha rivelato un ascesso e infiltrarsi nel polmone destro. (Figure 1, 2) TC del torace ha dimostrato un mezzo ascesso lobo polmonare destra, un empiema loculated alla base posteriore del polmone destro e molteplici calcificate linfonodi ilari suggestivi di tubercolosi precedente. (Fig 3)

Figura 1

Figura 2

Figura 3

I chirurghi toracici eseguito una toracotomia per evacuare l’empiema e drenare l’ascesso polmonare .Biopsie e campioni di microbiologia del Empiema rivelato Pseudomonas. Dopo lunga discussione abbiamo deciso di iniziare il paziente su eparina a basso peso molecolare. Nel corso dei prossimi sei giorni la temperatura costante e ha fatto un pieno recupero.

Studi di imaging

L’obiettivo della valutazione è verifica oggettiva della presenza di trombo nella vena succlavia. I seguenti studi di imaging sono utili per la valutazione.

La radiografia del torace

Radiografia del torace è generalmente la modalità radiologica iniziale di scelta. Può essere utile nella rilevazione di lesioni che possono essere comprimendo la vena succlavia, come una costola cervicale o una massa polmonare apicale. Tuttavia, in molti casi, la radiografia del torace è un test molto sensibile e non è utile per determinare la causa di trombosi della vena succlavia. Inoltre, in molti casi, la costola cervicale è mancato sulla radiografia iniziale.

Ecografia

L’ecografia (B-mode in tempo reale, Doppler duplex, o color Doppler) è stato utilizzato con sempre maggiore frequenza nella diagnosi di trombosi della vena succlavia. Rispetto a flebografia, ecografia duplex ha alta specificità ma relativamente bassa sensibilità.

Trombi vena succlavia non visualizzato mediante ecografia duplex di solito sono o trombi murale occlusive o trombi situato nella parte prossimale della vena possibilmente in ombra dalla clavicola e sterno. Questa modalità è il test di scelta sia per lo screening e il follow-up. Se produce risultati negativi a fronte di forte sospetto clinico, devono essere utilizzate modalità alternative.

Venografia della vena succlavia

Tradizionalmente, venografia della vena succlavia (vedi immagine sotto) è stato utilizzato per la diagnosi di trombosi della vena succlavia, ma richiede incannulamento di una vena periferica del braccio. Edema del braccio colpito rende a volte questo difficile. Sottrazione digitale può consentire l’uso di una minore quantità di contrasto infuso in una vena piccola. La venografia comporta il rischio di effetti avversi di contrasto indotta. La tecnica è utilizzata solo quando la trombosi è fortemente sospettata nonostante uno studio ecografico negativo.

Un venogramma in un paziente con occlusione della vena succlavia. A lungo in piedi l’ostruzione provoca lo sviluppo di collaterali.

Tomografia computerizzata

Tomografia computerizzata (CT) può rilevare stenosi succlavia, ma non è stato studiato completamente abbastanza per consentire la determinazione della sua specificità e sensibilità. CT è talvolta usato quando flebografia e la risonanza magnetica (MRI) non sono facilmente disponibili. CT richiede l’uso di contrasto. CT può immagine facilmente sia le strutture intratoraciche e extratoraciche con ottima risoluzione. Tridimensionale TAC (CTA) rivali RM e flebografia sia in risoluzione e sensibilità. TC può anche rilevare trombi e la presenza di una malattia estrinseca che potrebbe causare trombosi vena succlavia. Attualmente, CT contrast-enhanced è considerato da alcuni come lo studio della scelta per sospetta trombosi venosa IJ. [5] reperti TC sono a bassa densità trombo endoluminale, una parete del vaso luminoso ben definito (a causa della captazione di contrasto da parte del vasa vasorum) , tumefazione dei tessuti molli che circonda la vena IJ, e una distesa prossimale della vena IJ al trombo.

Ecografia

L’ecografia è una prova sicura, non invasiva, portatile, e ampiamente disponibile che è il test di scelta per molti con la trombosi venosa IJ. Riscontri ecografici includono una vena dilatata e incomprimibile, coagulo intraluminale (un reperto in ritardo), e nessuna risposta per la manovra di Valsalva (variazione attesa del volume endoluminale secondario a una maggiore ritorno venoso).

L’ecografia fornisce immagini molto poveri sotto la clavicola e sotto la mandibola.Doppler può essere utile per rilevare il flusso cambia secondario trombo durante la fase acuta della formazione del coagulo.

Risonanza magnetica

RM è altamente specifico per rilevare trombi vena succlavia, ma la sua sensibilità (80% per trombi che occludono completamente il lume e 0% per trombi parzialmente occlusiva) è troppo basso per questa modalità per essere considerato attendibile in questa impostazione. MRI fornisce maggiore contrasto dei tessuti molli e la sensibilità ai tassi di flusso ematico della TC fa, e ha l’ulteriore vantaggio di non richiedere l’esposizione di contrasto per via endovenosa o radiazioni. Tuttavia, l’esame viene di solito eseguita in una posizione lontana ospedaliero e quindi è difficile e scomodo in pazienti critici.

Test di medicina nucleare, come gallio-67 studi hanno inaccettabilmente alti tassi di falsi positivi, soprattutto nei pazienti con neoplasie maligne attive. Tempi di studio spesso sono lunghi, e le prove devono essere eseguite nella zona di medicina nucleare; questi sono svantaggi per i pazienti in condizioni critiche.

Un coagulo della vena IJ associato con un catetere a permanenza, sia situato nella vena IJ o la vena succlavia, mandati cultura del catetere (dopo la rimozione) per escludere l’infezione.

Discussione

La Trombosi della vena giugulare interna (IJV) si riferisce ad un trombo intraluminale verificano ovunque dall’origine del IJV nel cranio, fino a dove si unisce la vena succlavia per formare la vena brachiocefalica. IJV trombosi associata ad infezione suppurativa del tratto aerodigestivo superiore è stata descritta all’inizio del ventesimo secolo da Courmont, Goodman e Mosher [1, 2, 3].

Nel 1936 Lemierre ha definito ulteriormente. Ha descritto sindrome Lemierre come trombo IJV infetto, causata da estensione dell’infezione orofaringea [4]. Oggi è noto anche come necrobacillosi o setticemia post-anginosa [5].

L’incidenza della trombosi IJV è ancora sconosciuta. Quello che sappiamo è che il 66% dei pazienti con cateteri IJV avere la prova di formazione di trombi in ecografia o all’autopsia, e che fino a un terzo di pazienti dopo una dissezione del collo avrà un trombo in IJV [6, 7]. Harada e altri hanno dimostrato che il più significativo restringimento della IJV seguente dissezione del collo avviene nella prima settimana dopo l’intervento chirurgico e che pervietà viene gradualmente ripristinata entro tre mesi [8]. L’incidenza sembra essere in aumento secondario ad un maggiore utilizzo di cateteri venosi centrali inseriti nella vena giugulare interna e vena succlavia, e per la maggior uso di IJV da coloro che abusano di droghe per via endovenosa [9].

Fattori eziologici possono essere meglio descritte in funzione triade di Virchow. Qualsiasi fattore che causa danno endoteliale, alterazione del flusso sanguigno o stato di ipercoagulabilità può portare alla trombosi IJV. Cateteri IJV possono potenziare la formazione di trombi causando danno endoteliale durante l’inserimento, o il catetere si può agire come un nido per la formazione di coaguli [6]. Il meccanismo di formazione di trombi nelle infezioni orofaringee è probabile che sia il risultato di ipercoagulabilità sistemica (causato o aggravato da infezione), stasi venosa (a bordo di occlusione del processo infettivo di infiammazione) e endoteliale danno (via invasione endovascolare diretta da microbi o attraverso infiammazione perivascolare) [10]. IJV trombo con otite media e mastoidite è il risultato della progressione di trombosi del seno sigmoideo. Danno endoteliale e l’introduzione di infezione sono i principali fattori causali di trombosi in tossicodipendenti per via endovenosa. Malignità potenzia la formazione di trombi causando compressione diretta da tumore o nodi e provocando uno stato di ipercoagulabilità.

Organismi coinvolti nella trombosi settica IJV sono determinate dalla eziologia. In via endovenosa IJV catetere, gli organismi più probabili sono positivi grammi con Staphylococcus aureus il più comune. Se la sepsi cavità orale è il fattore causale, anaerobi sono i più comuni. Microrganismi Gram-negativi, in particolare Proteus e Pseudomonas sono gli organismi più comuni nella sepsi otologica.

Le manifestazioni cliniche della trombosi IJV dipendono dal fatto che sia infetto (complicato) o non infetti (semplice). Casi non complicati presentano dolore e gonfiore al collo, e un cavo si possono palpare sotto il muscolo sternocleidomastoideo. Tovi et al descritto la seguente manifestazione clinica in un’ampia serie di pazienti con settica trombosi IJV: febbre (83%), leucocitosi (78%), dolore cervicale (66%), collo gonfiore (72%), segno spinale (39% ), sindrome da sepsi (39%), complicazioni pleuro-polmonare (28%), sindrome della vena cava superiore (11%), chilotorace (5%) e la sindrome forame giugulare (6%). [11]

Indagini di laboratorio richieste in pazienti con trombosi IJV variano a seconda che il trombo è infetto (complicata) o meno infetto (semplice). I pazienti con trombosi IJV complicato richiedono cultura dalla fonte di infezione (orofaringe, orecchie, punta del catetere etc.) e le culture del sangue. Trombosi IJV semplice richiede indagini più approfondite, come ad esempio la proteina C, S, test antitrombina-3-carenza e schermo DIC che comprende il tempo di protrombina (PT), attivato tempo parziale di tromboplastina (APTT), prodotti di degradazione della fibrina e fibrinogeno.

Studi di imaging utili nella trombosi IJV includono contrasto tomografia computerizzata (TC), la risonanza magnetica (MRI), la scansione medicina nucleare, ecografia e venogram contrasto.

Contrasto venogram usato per essere il gold standard, ma perché è invasiva e può sloggiare trombo e causare un embolo, che ha perso il favore. Ecografia è sicuro, non invasivo, e conveniente e di un doppler in grado di rilevare la portata. Purtroppo è sub-ottimale per il rilevamento di trombosi venosa profonda alla mandibola e clavicola.

TAC con mezzo di contrasto per via endovenosa è considerato da molti come lo studio della scelta. Risultati di scansione TC includono l’identificazione di una bassa densità trombo endoluminale, una parete del vaso luminoso ben definito (a causa della captazione contrasto vasa vasorum), gonfiore dei tessuti molli circostanti IJV e una prossimale IJV distesa al trombo.

RM fornisce definizione dei tessuti molli e una migliore sensibilità alle portate arteriosa rispetto al TAC e non richiede l’esposizione a contrastare materiali o radiazioni [12].

Scansione medicina nucleare ha alti tassi di falsi positivi e tempo di studio prolungato. Inoltre gli studi devono essere eseguiti in una zona medicina nucleare che significa che un paziente, che è spesso criticamente malati, deve essere trasportato a subire l’indagine.

Il trattamento medico dei pazienti con trombosi IJV dipende dal fatto che il trombo è infetto o meno. In trombosi non infetta il fattore causale, per esempio un catetere vena giugulare, dovrebbe essere rimosso prima. Il ruolo della terapia anticoagulante è controversa. Ci sono studi sufficienti per guidare i medici e il fatto che si tratta di una condizione abbastanza sotto-diagnosticata con poche complicazioni gravi solleva la questione se la terapia anticoagulante è necessario. Per quanto riguarda la terapia trombolitica, esistono solo poche serie caso isolato e non è ancora stata stabilita la sicurezza [13].

In Trombosi infetto IJV il sito primario di infezione devono essere trattati prima, per esempio, ascessi collo devono essere svuotati e mastoidectomia fatto per mastoiditis. La maggior parte dei pazienti con trombosi infetto IJV farà bene sotto antibiotici solo .La scelta dell’antibiotico dipende dal fattore causale. Se il trombo è stato causato da un catetere a permanenza il più probabile organismo sarà gram positive e vancomicina deve essere usato fino a quando l’organismo è isolato e la sua sensibilità ha stabilito [14]. In caso di infezione all’orecchio primario il paziente deve essere trattato con Amikacina per coprire gram negativi organismi fino dell’organismo e la sua sensibilità è stato stabilito [15]. Se il trombo vena giugulare è stata causata da infezione orofaringea il paziente deve essere avviato su un antibiotico ad ampio spettro con copertura anaerobica fino dell’organismo e la sua sensibilità è stata determinata. È importante che tutti i pazienti con trombosi infetto ricevono un totale di quattro a sei settimane di terapia antibiotica [16].

Non è stato stabilito il ruolo di anti-coagulazione sistemico in un trombo infetto. Dovrebbe essere presa in considerazione solo se vi è la propagazione coagulo o emboli settici. E ‘importante tenere a mente che vi è un rischio di sanguinamento ed ematomi espansiva con potenziale compromissione delle vie aeree.

La chirurgia dovrebbe essere riservato ai soli casi complicati. Le indicazioni per la chirurgia comprendono infezioni associate spazio profondo collo, coinvolgimento guaina carotidea (per impedire l’estensione nella carotide), ascessi intra-luminali e fallito il trattamento medico. Va ricordato che la risposta al trattamento medico potrebbe essere lenta. Un certo numero di procedure sono state descritte in letteratura e comprendono il drenaggio delle raccolte, sbrigliamento del tessuto necrotico e anche legatura o escissione del IJV.

Trombosi IJV può essere associato a complicazioni come embolia polmonare, trombosi venosa succlavia, trombosi superiore seno sagittale, la sindrome della vena cava superiore, pseudotumor cerebri e della laringe e inferiore edema delle vie aeree. Tromboflebite infettati possono causare complicazioni come la sindrome sistemica sepsi, embolia settica di polmoni, fegato, milza, cervello, pelle, muscoli, e del midollo osseo, empiema, artrite settica, insufficienza renale, disfunzione epatica e edema cerebrale [17].

Sindrome di Lemierre ha avuto un tasso di mortalità superiore al cinquanta per cento in epoca pre-antibiotica. La mortalità oggi è difficile da determinare perché la maggior parte dei pazienti hanno un coinvolgimento multi-sistema e di una malattia grave concomitante. Questo rende il contributo della trombosi sé alla mortalità difficile da determinare.

Conclusione

Quando riconosciuto presto e trattati con appropriata terapia medica e chirurgica aggressiva, morte per trombosi venosa giugulare è raro oggi. Essendo consapevoli di trombosi della vena giugulare, il medico può essere più vigili per possibili complicazioni e diagnosticare e trattare loro in precedenza.

Corrispondenza a

Dr Nico Jonas Divisione di Otorinolaringoiatria dell’Università di Città del Capo Medical School H53, Old Main Building, Groote Schuur Hospital Observatory, Città del Capo, Sud Africa 7925 Tel: +27 (021) 4066420 Fax: +27 (021) 4488865 E-mail: nicojonas @ gmail.com

References

1. Courmont P, Cade A. On a case caused by an anaerobic streptobacillus [in French]. Arch Med Exp Anat Pathol.1900;12:393-418

2. Goodman C. Primary jugular thrombosis due to tonsil infection. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1917;26:527-529

3. Mosher HP. Deep cervical abscess and thrombosis of the internal jugular vein. Laryngoscope. 1920:30:365-375

4. Lemierre A. On certain septicaemias due to anaerobic organisms. Lancet. 1936;1:701-703

5. Kristensen LH, Prag J. Human necrobacillosis, with emphasis on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Infect Dis.2000;31:524-532

6. Hubsch PJ, Stiglbauer RL, Schwaighofer BW. Internal jugular and subclavian vein thrombosis caused by central venous catheters. Evaluation using Doppler blood flow imaging. J Ultrasound Med 1988 Nov; 7(11): 629-36

7. Leontsinis TG, Currie AR, Mannell A. Internal jugular vein thrombosis following functional neck dissection.Laryngoscope 1995 Feb; 105(2): 169-74

8. Harada H, Omura K, TakeuchiY. Patency and calibre of the internal jugular vein after neck dissection. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2003 Aug; 30(3):269-72

9. Myers EM, Kirkland LS Jr, Mickey R. The head and neck sequelae of cervical intravenous drug abuse. Laryngoscope 1988 Feb; 98(2): 213-8

10. Goldenberg NA, Knapp-Clevenger R, Hays T. Lemierre’s and Lemeirre’s-like syndromes in children: Survival and thromboembolic outcomes. Pediatrics 2005 Oct; 116(4)e543-e548

11. Tovi F, Fliss DM, Gatot A. Septic jugular thrombosis with abscess formation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1991 Aug; 100(8): 682-4

12. Carpenter JP, Holland GA, Baum RA . Magnetic resonance venography for the detection of deep venous thrombosis: comparison with contrast venography and duplex Doppler ultrasonography. J Vasc Surg 1993 Nov;18(5): 734-41

13. Gurley MB, King TS, Tsai FY. Sigmoid sinus thrombosis associated with internal jugular venous occlusion: direct thrombolytic treatment. J Endovasc Surg 1996 Aug; 3(3): 306-14

14. Coplin WM, O’Keefe GE, Grady MS. Thrombotic, infectious, and procedural complications of the jugular bulb catheter in the intensive care unit. Neurosurgery 1997 Jul; 41(1): 101-7; discussion 107-9

15. Bradley DT, Hashisaki GT, Mason JC. Otogenic sigmoid sinus thrombosis: what is the role of anticoagulation? Laryngoscope. 2002 Oct; 112(10):1726-9.

16. Chirinos JA, Lichtstein DM, Garcia J. The evolution of Lemierre syndrome: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2002 Nov; 81(6):458-65

17. Ascher E, Salles-Cunha S, Hingorani A. Morbidity and mortality associated with internal jugular vein thromboses. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2005 Jul-Aug; 39(4):335-9.{full_citation}

Otology & Neurotology

27:937–944 © 2006, Otology & Neurotology, Inc.

Internal Jugular Vein Thrombosis Associated with Acute Mastoiditis in a Pediatric Age

*Luca Oscar Redaelli de Zinis, †Roberto Gasparotti, *Chiara Campovecchi, *Giacomo Annibale, and *Maria Grazia Barezzani

![]() *Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery and ÞDepartment of Radiology, University of Brescia, Italy

*Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery and ÞDepartment of Radiology, University of Brescia, Italy

Objective: To discuss the clinical aspects and management of internal jugular vein thrombosis associated with acute otitis media. Study Design: Case reports and review of the literature. Setting: University hospital, tertiary referral center.

Patient: The authors describe two cases of internal jugular vein thrombosis, without sigmoid sinus thrombosis, secondary to acute otomastoiditis.

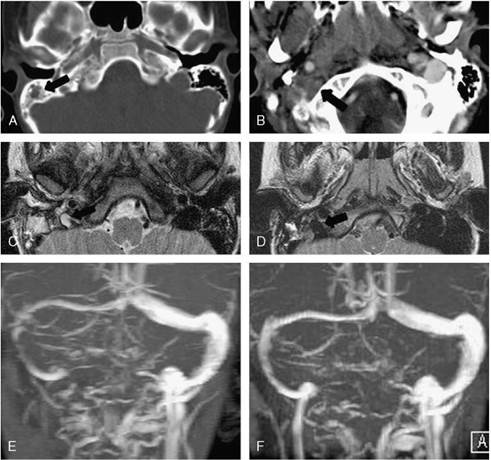

Intervention: Jugular vein thrombosis was diagnosed in both cases by observation of filling defects of the involved jugular bulb on contrast-enhanced computed tomography and confirmed by conventional magnetic resonance and magnetic resonance venography.

Results: Both patients recovered after recanalization of the vessel concomitant to anticoagulation and antibiotic treatment associated with a simple mastoidectomy.

Conclusion: Internal jugular vein thrombosis may be a complication of acute otitis media, without involvement of the sigmoid sinus and with a starting point in the jugular bulb. Anticoagulation associated with antibiotic therapy can be considered a safe and effective treatment. Surgery should only be performed to eliminate the source of infection from the middle ear and mastoid. Key Words: Acute otitis media—Vein thrombosis.

Otol Neurotol 27:937– 944, 2006.

![]()

A well-known vascular complication of otitis media and/or mastoiditis is septic thrombosis of the sigmoid portion of the lateral venous sinus. Although it has become rare with the advent of antibiotics, it can still be fatal especially when associated with other intracranial complications (1,2). The thrombotic process can extend backwards to the superior sagittal sinus interfering with cerebrospinal fluid resorption by blockage of the arachnoid granulations, producing an otogenic hydrocephalus (3). It can extend through the petrosal sinuses to the cavernous sinus (4–6), the internal jugular and subclavian veins (7), and eventually to the superior vena cava (8). Starting from the jugular vein, bacteremia with lung embolization can develop into a clinical picture resembling Lemierre syndrome (9,10). A carotid artery spasm or arteritis (11) such as a carotid sheath abscess (12) can also be the consequence of an adjacent thrombophlebitis.

The observation of two unusual cases of jugular bulb thrombosis extending to the jugular vein but not the sigmoid sinus during acute otitis media prompted us to analyze this uncommon behavior and to focus on this

![]() Address correspondence and reprint requests to Luca Oscar Redaelli de Zinis, M.D., Department of Otorhinolaryngology, University of Brescia, Piazzale Spedali Civili 1, 25123 Brescia, Italy; E-mail: redaelli@med.unibs.it

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Luca Oscar Redaelli de Zinis, M.D., Department of Otorhinolaryngology, University of Brescia, Piazzale Spedali Civili 1, 25123 Brescia, Italy; E-mail: redaelli@med.unibs.it

possible complication of simple acute otitis media with potentially severe general consequences.

CASE 1

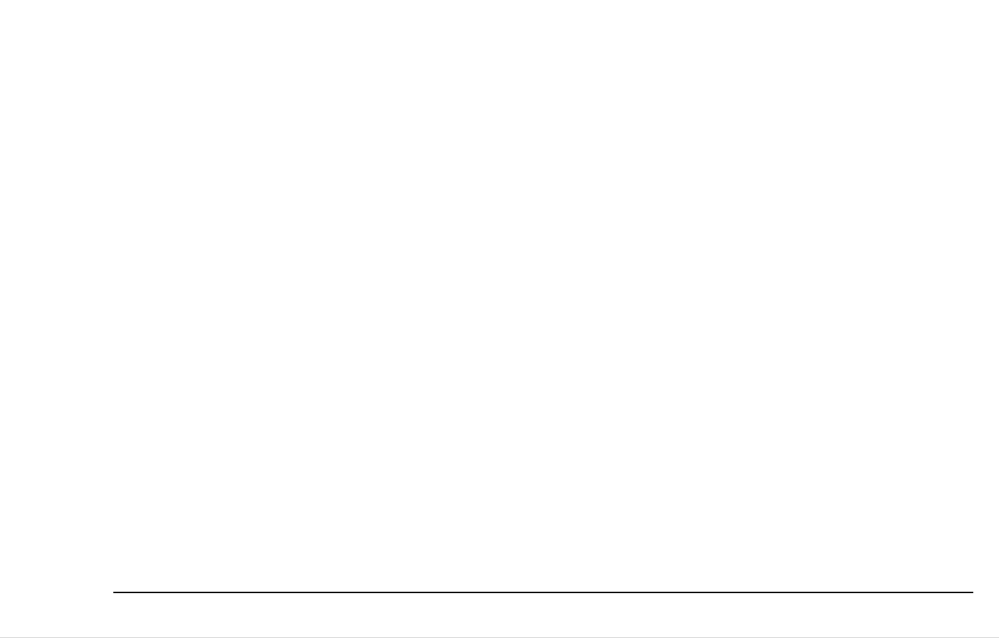

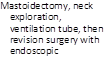

A five-year-old boy was admitted after one-week treatment with nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs for left acute otitis media with worsening otalgia and fever (39.6°C) during the previous 48 hours. Clinical examination showed a thickened and bulging pars tensa with a reddish pars flaccida. Palpation of the mastoid tip was painful. Antibiotic treatment with ceftazidime, 750 mg three times daily, was started. A blood cell count showed moderate neutrophilic granulocytosis, whereas Epstein-Barr viral tests were negative. The following day, torticollis was evident followed by an episode of vomiting. A cervical swelling appeared one day later, and a computed tomography (CT) of the temporal bone and the neck was performed (Fig. 1). High resolution CT of the petrous bone demonstrated a coalescent left mastoiditis with mastoid septa erosion and complete opacification of the middle ear. After contrast administration, no opacification of the left jugular bulb was observed, indicating acute thrombosis, which involved the proximal end of the jugular vein together with multiple enlarged lymph nodes. Ultrasonographic examination

![]() 937

937

938 L. O. REDAELLI DE ZINIS ET AL.

FIG. 1. Patient 1. Computed tomographic scan obtained after contrast media administration at the level of the jugular foramen (A) and neck (B). A filling defect of the left jugular bulb (arrow) indicating acute thrombosis is evident, whereas the left sigmoid sinus is patent (arrowheads). The jugular vein thrombosis extends to the neck (short arrow).

of the neck confirmed the thrombosis of the proximal part of the internal jugular vein. A simple mastoidectomy and a myringotomy with the insertion of a ventilation tube were performed. The surgical intervention revealed purulent exudates without the presence of granulation tissue or bone erosion, and the puncture of the sigmoid sinus gave rise to blood flow. The day after the intervention body temperature was normal; the antibiotic regime was changed to ampicillin-sulbactam (1,300 mg three times daily) and netilmicin (60 mg twice daily). Subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin administration was started two days after surgery with 2,000 units twice daily. Coagulation tests showed a thrombophilic state caused by a deficit in factor V Leiden, the so-called activated protein C resistance. Oral anticoagulation was initiated on the sixth postoperative day with warfarin; subcutaneous heparin was discontinued after eight days when therapeutic values of international normalized ratio by oral anticoagulant were obtained. On the fifth postoperative day, the results of intraoperative bacterial culture showed the presence of Streptococcus pyogenes; thus, netilmicin was discontinued. Ultrasonographic examination, one and two weeks after operation, showed progressive recanalization of the jugular vein. Amoxicillin clavulanate was administered (500 mg three times daily) instead of ampicillin sulbactam from the eighth postoperative day for 20 days. After two months, a sonography showed that recanalization of the internal jugular vein was complete, and blood flow was normal. At that time, normal hearing was documented using pure tone audiometry. The following month, warfarin was discontinued. The ventilation tube was extruded within the fifth postoperative month, with spontaneous eardrum clo‑

Otology & Neurotology, Vol. 27, No. 7, 2006

sure; 30 months later, no further episodes of otitis media or venous thrombosis have been observed.

![]() CASE 2

CASE 2

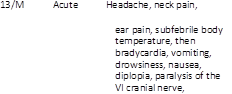

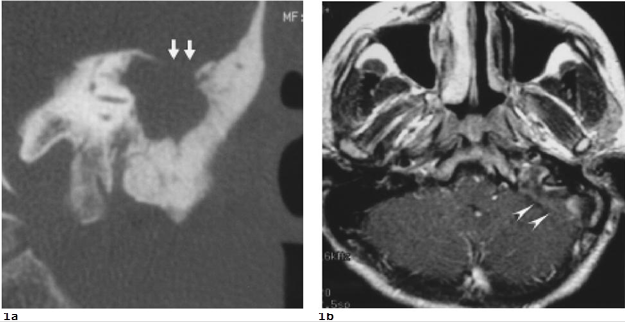

A seven-year-old boy was admitted for right acute otitis media with fever when, after three days of ineffective treatment with an oral cephalosporin, diplopia, increasing ear pain, and headache occurred. Physical examination revealed that there was a bulging reddish right eardrum with a paresis of the right abducens nerve. Antibiotic treatment was started with ceftazidime (675 mg four times daily) and amikacin (185 mg twice daily), and CT of the brain and temporal bone was performed. A blood cell count showed moderate neutrophilic granulocytosis, and Epstein-Barr viral tests were negative. The computed tomographic scan excluded brain lesions and confirmed a right coalescent mastoiditis (Fig. 2A). The next day, a neck and a pharyngeal swelling together with a torticollis appeared, and the patient was evaluated using CT of the neck to rule out extension of the mastoid infection. The computed tomographic scan revealed enlarged lymph nodes and occlusion of the proximal portion of the internal jugular vein involving the jugular bulb (Fig. 2B). Magnetic resonance (MR) and MR venography of the brain and skull base confirmed temporal bone inflammation and thrombosis of the jugular bulb extending approximately 2 cm to the internal jugular vein (Fig. 2C and E). Ampicillin-sulbactam (1,500 mg three times daily) was started instead of ceftazidime, and amikacin was also administered (370 mg once a day). On the same day, the patient was submitted to a mastoidectomy with posterior tympanotomy that revealed purulent exudates and granulation tissue without bone erosion; puncture of the sigmoid sinus gave rise to normal blood flow. Coagulation tests were normal. Subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin was started (3,000 units twice daily). Oral anticoagulation was associated in fourth postoperative day with warfarin, and subcutaneous heparin was discontinued after two days when therapeutic values of international normalized ratio by oral anticoagulant were obtained. The intraoperative bacterial culture was negative, and on the seventh postoperative day, amikacin was discontinued. The patient was discharged on the eighth postoperative day, with ampicillin-sulbactam (1,500 mg two times a day for five days); oral amoxicillin clavulanate was also administered (500 mg three times daily for the next 15 days). MR examination including MR venography, performed three months later, documented complete recanalization of the internal jugular vein (Fig. 2D and F) when anticoagulation treatment was discontinued. Two years later, the child has not experienced any new episodes of otitis media.

DISCUSSION

Venous thrombosis may be associated with infection because of vascular damage. When the vein is affected

INTERNAL JUGULAR VEIN THROMBOSIS IN ACUTE MASTOIDITIS 939

FIG. 2. Patient 2. A, Computed tomographic scan, bone algorithm, and opacification of the right mastoid (arrow). B, Contrast-enhanced computed tomographic scan. Absent opacification of the right jugular bulb (arrow), suggesting acute thrombosis. On the left side is a jugular bulb with a normal appearance, enhanced with contrast material. C, MR, T2-weighted axial section at the level of the jugular foramen. Hyperintense inflammatory tissue in the right mastoid. The flow void is absent in the right jugular bulb (arrow), which is hypoplastic as compared with the contralateral side. D, Follow-up MR at three months, T2-weighted axial section. Reappearance of the flow void in the right jugular bulb (arrow), indicating recanalization. E, MR venography. Right jugular vein thrombosis. Dominant left transverse sinus. F, MR venography, follow-up at three months. Complete recanalization of the right jugular vein.

by an adjacent septic focus, the initial site of involvement is the adventitia, which becomes congested and infiltrated by inflammatory cells. Next, all the layers of the vein become involved, and the inflammation reaches the intima where the adherence of fibrin, blood cells, and platelets causes thrombus development (13). Formation of the thrombus may be considered as a protective mechanism, attempting to localize the infection (6). An infection within the temporal bone may cause inflammation of intracranial structures such as the dura over the lateral sinus by direct spread through dehiscent bone or through the round and the oval windows, through the endolymphatic sac, via a fistula in the otic capsule or even through the cochlear aqueduct or perineural spaces in the internal acoustic meatus (7). On the other hand, extension through intact bone can develop by retrograde thrombophlebitis via the small venules of the temporal bone, from the superior petrosal sinus, the cavernous sinus, the caroticotympanic canaliculi, the

pericarotid venous plexus, and other possible vascular anastomoses (6). Thrombosis may also be caused by osteothrombophlebitis in the early stage of acute otitis media, with an intact bony sinus plate (6). In many cases, dural venous thrombophlebitis is associated with an epidural abscess (11).

Not all infections are followed by venous thrombosis, but in most cases, venous thrombosis develops during an otitis media in a patient with a generalized hypercoagulable state that may be either inherited or acquired (14). Inherited hypercoagulable disorders include deficiency of antithrombin III (qualitative or quantitative), which usually binds and inactivates thrombin and factor Xa, and deficiency of protein C or S, which usually suppresses the coagulation cascade by inhibiting factors Va and VIIIa (15,16). Other inherited hypercoagulable disorders are resistance to activated protein C caused by factor V Leiden mutation, elevated prothrombin levels caused by prothrombin gene 20210A mutation,

![]() Otology & Neurotology, Vol. 27, No. 7, 2006

Otology & Neurotology, Vol. 27, No. 7, 2006

940 L. O. REDAELLI DE ZINIS ET AL.

increased levels of factors VII, XI, IX, VIII, von Willebrand factor, lipoprotein (a), and thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor, dysfibrinogemia, hyperhomocysteinemia, and plasminogen deficiency (15,17). Most thrombophilic genetic anomalies are autosomal dominant: heterozygous individuals are mildly or moderately symptomatic, but in combination, they significantly increase the risk of thrombosis (15,18). Furthermore, other poorly defined genetic alterations may be associated with hypercoagulability (19).

The classic type of acquired hypercoagulable disorder is antiphospholipid syndrome, which is an idiopathic disease characterized by the production of different antibodies (lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, etc.) against different phospholipid-protein complexes involved in the process of coagulation and anticoagulation (20). Other acquired hypercoagulable states are those associated with myeloproliferative disease or other malignancies, the use of oral contraceptives, asparaginase, epoetin alfa and tamoxifen, pregnancy and puerperium, high altitude, surgery, immobilization, splints or casts, central catheters, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, trauma, renal diseases, pulmonary hypertension, congenital heart disease, sepsis, traumatic and nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage in newborns, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, vasculitis such as that caused by Beh0et disease, thrombocytosis, sickle cell disease, altered cerebral hemodynamic states (i.e., congestive heart failure, dehydration, malnutrition, and diabetic ketoacidosis), and chronic debilitating diseases in general (14,16,18,21–25). When dealing with an infection, it is known that bacterial products can cause induction of cytokines via immune cells leading to coagulation disturbances (26). Particularly, Fusobacterium necrophorum, the microorganism involved in Lemierre syndrome, is a specific inducer of hemagglutinin-mediated platelet aggregation (27). A complete work-up to find inherited or acquired coagulation disturbances including protein C level, AT activity, protein S free antigen, presence of factor V Leiden, factor II polymorphisms, methyltetrahydrofolate reductase mutations, serum homocysteine levels, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, and lipoprotein (a) levels has been suggested for sinus thrombosis associated with otitis media (25).

The presenting signs and symptoms of an otogenic lateral sinus thrombosis are often vague; otologic symptoms predominate, and only nonspecific symptoms like headaches or fever can be more strictly related to intracranial complications (14,21,28,29). Sometimes, it is only the finding of a prolonged course of otologic symptoms of an acute otitis media that raises the suspicion of a complication (14,21,28,29). On the other hand, the appearance of a neck mass and/or torticollis, when an exteriorization of the otomastoiditis has been excluded, can be suggestive of internal jugular vein thrombosis. “Cord sign“, an induration corresponding to the course of the internal jugular vein beneath the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, is considered typical but is rarely present (13). For our two patients, a diag‑

Otology & Neurotology, Vol. 27, No. 7, 2006

nosis of vascular complication was preceded by neck swelling and torticollis in the first case and by diplopia and torticollis in the second. The occurrence of abducens nerve palsy in our cases can be attributed to perineural inflammation caused by petrous apex infection or by extension of the thrombus to the inferior petrosal sinus that courses downward, near to the abducens nerve and not to an increased intracranial pressure as observed by other investigators (16,21). Those symptoms prompted us to perform a computed tomographic scan, which showed the thrombosis of the jugular vein. Contrast-enhanced CT with thin slices is highly sensitive in the diagnosis of venous dural sinus thrombosis and therefore should be performed when there are clinical signs. The diagnosis consists of detecting hyperdensity of the sigmoid and transverse sinus, which can be confirmed by observation of a filling defect after contrast media injection. In the present cases, contrastenhanced CT showed a filling defect in the jugular bulb and an absent opacification of the jugular vein in the neck (Figs. 1 and 2). Although the diagnosis of jugular vein thrombosis does not require MR, this examination is indicated to detect concomitant lesions in the cerebellum and to document with MR venography the extension of the entire process whenever extension of the thrombotic process in the lateral sinus is suspected. MR venography is a useful tool for the assessment of the extension of thrombosis and for the follow-up after anticoagulation to demonstrate recanalization (Fig. 2). In addition, MR is performed on patients with clinical symptoms or CT findings suggestive of intracranial complications because of its higher sensitivity in detecting extra-axial fluid collections and associated vascular problems. Conventional MR imaging revealed that flow-related enhancement and in-plane, turbulent, or slow flow can cause loss of the flow void and thus mimic thrombosis. Consequently, phase-contrast MR venography is the imaging modality of choice for the assessment of cerebral venous thrombosis. Anatomic variations and atypical cerebral venous drainage must also be taken into account to avoid false-positive diagnosis of jugular vein thrombosis (30). In the second case, there was in fact a dominant left transverse sinus, and the right jugular bulb was smaller than the contralateral bulb (Fig. 2). MR venography is considered as the technique of choice for diagnosis and follow-up of cerebral vein thromboses, although in certain cases conventional MR may be superior because it shows the thrombus itself and not just the absence of a signal, as observed with MR venography. On the other hand, MR venography is noninvasive, does not involve ionizing radiation, and can be performed at the same time as MR imaging, using comparatively short acquisition times.

![]() To our knowledge, this is the first time that internal jugular vein thrombosis has been observed from acute otitis media without sigmoid sinus thrombosis, although the explanation for this unexpected behavior remains unknown. One hypothesis is that the inflammation in the region of the hypotympanum caused the vascular

To our knowledge, this is the first time that internal jugular vein thrombosis has been observed from acute otitis media without sigmoid sinus thrombosis, although the explanation for this unexpected behavior remains unknown. One hypothesis is that the inflammation in the region of the hypotympanum caused the vascular

INTERNAL JUGULAR VEIN THROMBOSIS IN ACUTE MASTOIDITIS 941

reaction at the level of the jugular bulb, with a propagation of the inflammation along the wall of the vessel in the neck. Internal jugular vein extension of a sigmoid sinus thrombosis during otitis media has been described in less than 30 cases during the last two decades (1,2,6–10,12,13,18,21,25–27,31–34). The most welldetailed cases are reported in Table 1 and are almost equally distributed between chronic and acute or sub-acute otitis media; most patients were adolescents or children (Table 1). The infectious agents, when detected by microbiological culture, included various groups with a high number of cases having mixed flora (Table 1). F. necrophorum, such as in Lemierre syndrome, was observed in only three patients (10,27,34). Septicemia by F. necrophorum during an otitis media without a thrombotic event has also been reported (35). A hypercoagulable disorder was observed in two previously reported cases: antiphospholipid syndrome with anomalies in tissue thromboplastin inhibitor (18) in one case and APC resistance with a factor V Leiden mutation in the other (34). Associated intracranial complications (meningitis, epidural or cerebellar abscess, hydrocephalus, and cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea) have been reported in only a few patients (2,10,12,32). Septic pulmonary emboli have also been reported in two patients (8,9). Most patients had been treated by mastoidectomy, sigmoid sinus opening, and drainage (1,8,12,13,27); whereas some also underwent jugular vein ligation (2,6,7,9,10,31). Antibiotic treatment for periods varying from 2 to 8 weeks was used in all cases, usually in association with antibiotics that were tailored after the results of microbiological cultures were available. Anticoagulation therapy was used in less than half of the cases for a period of two weeks to six months (6–8,18,21,26,27,32–34). Only one patient needed lifelong anticoagulation for antiphospholipid syndrome (18). Recovery without important sequelae was reported for most patients; only one death was reported that occurred in the early 1980s (12). Most patients that did not have opening of the sigmoid sinus or ligation of the jugular vein had recanalization of the vessel (21,26,32).

The observation of a progressive, more conservative approach of this clinical entity over time (Table 1) is undoubtedly caused by more effective medical treatment, which permits less aggressive surgery. Exposure and control of the internal jugular vein and thrombus removal in cases having thrombosis of the sigmoid sinus, as suggested in the 1980s and early 1990s (Table 1), carry some risks, including septic emboli and violation of the dura with subarachnoid spread of infection (36). On the contrary, the aim of surgery should be to remove infection from middle ear and mastoid and restore ventilation, whereas management of thrombosed vessels does not seem to need surgery, as what was observed in our patients, and has been recently reported for sigmoid sinus thrombosis alone or associated with jugular vein thrombosis (21,26,32,36). At present, opening and drainage of the sinus and drainage or ligation of the jugular vein should be reserved for cases of empyema (37) or for rare

cases that develop septic embolism (27). Even transfemoral or transjugular direct venous thrombolysis with urokinase infusion and balloon dilation if there is a stenosis, as what was proposed by some investigators (38–40), or combined intravenous heparin and direct intrathrombus administration of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (41) seem to be unnecessary in these cases (21,26,32). In general, endovascular thrombolysis has not yet been demonstrated to be more effective than systemic treatment (16).

General guidelines for the treatment of thromboembolic events, both in adults and in children, include intravenous heparin or subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin for several days and subsequent overlapping with oral anticoagulants until the prothrombin time is prolonged to the therapeutic value with a target international normalized ratio of 2.5 (16). Anticoagulant therapy is stopped after three to six months when risk factors for thrombotic events are eliminated. In our patients, anticoagulants were discontinued after three months when the ear was completely recovered, and there was documentation of jugular vein recanalization. When a continuing risk factor or a second recurrence of thromboembolic event is present, indefinite oral anticoagulant therapy should be considered, although this possibility is controversial because most thrombophilic individuals (those with low levels of baseline genetic hypercoagulability) never have venous thromboembolism throughout their lifetimes; if an episode does occur, it is unlikely to recur (15). Some investigators have reported recanalization of the sigmoid sinus with antibiotic treatment alone and dispute the usefulness of anticoagulants that are thought to carry potential risks (release of septic emboli, hemorrhage into the mastoid cavity, bleeding, drug interactions, thrombocytopenia, osteoporosis, and hemorrhagic skin necrosis) (2,14,33,36). In reality, in the case of otitis media thrombophlebitis, complications of anticoagulant therapy have not been reported. Moreover, for children, anticoagulant therapy for dural sinus thromboses is considered safe and without sequelae (23).

Intravenous antibiotic treatment that is effective against infectious agents normally present in acute and chronic otitis media (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, or Moraxella catarrhalis, Staphylococcus ureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, anaerobes) should be started and tailored after the results of bacteriologic examination of middle ear and mastoid exudates are available. After approximately 2 weeks of intravenous antibiotics, when a favorable evolution is observed, oral administration can be started for a total period of four to six weeks (21,36).

In conclusion, we observed two unusual cases of internal jugular vein thrombosis secondary to acute otitis media where the combination of antibiotic and antithrombotic therapy was found to be a safe and effective treatment with recanalization of the vein. Moreover, we have also analyzed cases of sigmoid sinus thrombosis with internal jugular vein extension reported in the literature. The perception of a progressive trend toward more

![]() Otology & Neurotology, Vol. 27, No. 7, 2006

Otology & Neurotology, Vol. 27, No. 7, 2006

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

944 L. O. REDAELLI DE ZINIS ET AL.

conservative treatment, where antibiotics and anticoagulants are the mainstay of therapy and surgery is reserved to eliminate the source of infection by draining the tympanomastoid cavity, is deducible from the literature and confirmed by our experience. Surgical opening, drainage, and ligation of the jugular vein should be reserved for cases where purulent exudates within the vessel pose an impending risk of septicemia or diffusion of septic emboli. Some controversies are still present about the choice and the duration of anticoagulant therapy (16).

REFERENCES

1. Kangsanarak J, Fooanant S, Ruckphaopunt K, et al. Extracranial and intracranial complications of suppurative otitis media. Report of 102 cases. J Laryngol Otol 1993;107:999–1004.

2. Kaplan DM, Kraus M, Puterman M, et al. Otogenic lateral sinus thrombosis in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1999;49: 177–83.

3. Symonds CP. Otitic hydrocephalus. Brain 1931;54:55–71.

4. Doyle KJ, Jackler RK. Otogenic cavernous sinus thrombosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1991;104:873–7.

5. Singh B. The management of lateral sinus thrombosis. J Laryngol Otol 1993;107:803–8.

6. Kuczkowski J, Mikaszewski B. Intracranial complications of acute and chronic mastoiditis: report of two cases in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2001;60:227–37.

7. Surkin MI, Green RP, Kessler SM, et al. Subclavian vein thrombosis secondary to chronic otitis media. A case report. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1983;92:45–8.

8. Tovi F, Hirsch M, Gatot A. Superior vena cava syndrome: presenting symptom of silent otitis media. J Laryngol Otol 1988; 102:623–5.

9. Hughes CE, Kenneth Spear R, Shinabarger CE, et al. Septic pulmonary emboli complicating mastoiditis: Lemierre’s syndrome revisited. Clin Infect Dis 1994;18:633– 5.

10. Stokroos RJ, Manni JJ, de Kruijk JR, et al. Lemierre syndrome and acute mastoiditis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;125: 589–91.

11. Vazquez E, Castellote A, Piqueras J, et al. Imaging of complications of acute mastoiditis in children. Radiographics 2003;23: 359–72.

12. Teichgraeber JF, Per-Lee JH, Turner JS Jr. Lateral sinus thrombosis: a modern perspective. Laryngoscope 1982;92:744–51.

13. Tovi F, Fliss DM, Noyek AM. Septic internal jugular vein thrombosis. J Otolaryngol 1993;22:415–20.

14. Ram B, Meiklejohn DJ, Nunez DA, et al. Combined risk factors contributing to cerebral venous thrombosis in a young woman. J Laryngol Otol 2001;115:307–10.

15. Schafer AI, Levine MN, Konkle BA, et al. Thrombotic disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Hematology 2003:520–39.

16. Stam J. Thrombosis of the cerebral veins and sinuses. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1791–8.

17. Crowther MA, Kelton JG. Congenital thrombophilic states associated with venous thrombosis: a qualitative overview and proposed classification system. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:128–34.

18. Gold S, Kamerer DB, Hirsch BE, et al. Hypercoagulability in otologic patients. Am J Otolaryngol 1993;14:327–31.

19. Lane DA, Grant PJ. Role of hemostatic gene polymorphisms in venous and arterial thrombotic disease. Blood 2000;95:1517–28.

20. Greaves M, Cohen H, Machin SJ, et al. Guidelines on the investigation and management of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Br J Haematol 2000;109:704–15.

21. Garcia RD, Baker AS, Cunningham MJ, et al. Lateral sinus thrombosis associated with otitis media and mastoiditis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1995;14:617–23.

22. Rosen A, Scher N. Nonseptic lateral sinus thrombosis: the otolaryngologic perspective. Laryngoscope 1997;107:680–3.

23. DeVeber G, Chan A, Managle P, et al. Anticoagulation therapy in pediatric patients with sinovenous thrombosis. Arch Neurol 1998; 55:1533–6.

24. Carvhalho KS, Bodensteiner JB, Connolly PJ, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis in children. J Child Neurol 2001;16:574–80.

25. Oestreicher-Kedem Y, Raveh E, Kornreich L, et al. Prothrombotic factors in children with otitis media and sinus thrombosis. Laryngoscope 2004;114:90–5.

26. Spandow O, Gothefors L, Fagerlund M, et al. Lateral sinus thrombosis after untreated otitis media. A clinical problem again? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2000;257:1–5.

27. Holzmann D, Huisman TA, Linder TE. Lateral dural sinus thrombosis in childhood. Laryngoscope 1999;109:645–51.

28. Rocha JL, Kondo W, Gracia CM, et al. Central venous sinus thrombosis following mastoiditis: report of 4 cases and literature review. Braz J Infect Dis 2000;4:307–12.

29. Jose J, Coatesworth AP, Anthony R, et al. Life threatening complications after partially treated mastoiditis. BMJ 2003;327:41–2.

30. Hoffmann O, Klingebiel R, Braun JS, et al. Diagnostic pitfall: atypical cerebral venous drainage via the vertebral venous system. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002;23:408–11.

31. Samuel J, Fernandes CMC. Lateral sinus thrombosis. J Laryngol Otol 1987;101:1227–9.

32. Zapanta PE, Chi DH, Faust RA. A Unique case of Bezold’s abscess associated with multiple dural sinus thromboses. Laryngoscope 2001;111:1944–8.

33. Bradley DT, Hashisaki GT, Mason JC. Otogenic sigmoid sinus thrombosis: what is the role of anticoagulation? Laryngoscope 2002;112:1726–9.

34. Klinge L, Vester U, Schaper J, et al. Severe fusobacteria infections (Lemierre syndrome) in two boys. Eur J Pediatr 2002;161:616–8.

35. Valla F, Berchiche C, Floret D. Nécrobacillose et syndrome de Lemeierre: àpropos d’un cas. Arch Pediatr 2003;10:1068–70.

36. Agarwal A, Lowry P, Isaacson G. Natural history of sigmoid sinus thrombosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2003;112:191–4.

37. Mathews TJ. Lateral sinus pathology (22 cases managed at Groote Schuur Hospital). J Laryngol Otol 1988;102:118–20.

38. Griesemer DA, Theodorou AA, Ber RA. Local fibrinolysis in cerebral venous thrombosis. Pediatr Neurol 1994;10:78–80.

39. Smith TP, Higashida RT, Barnwell SL, et al. Treatment of dural sinus thrombosis by urokinase infusion. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994;15:801–7.

40. Gurley MB, King TS, Tsai FY. Sigmoid sinus thrombosis associated with internal jugular venous occlusion: direct thrombolytic treatment. J Endovascular Surg 1996;3:306–14.

41. Frey J, Muro GJ, McDougall CG, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis: combined intrathrombus rtPA and intravenous heparin. Stroke 1999;30:489– 94.

![]()

![]() Otogenic Deep Neck Abscess: A Rare

Otogenic Deep Neck Abscess: A Rare

Complication of Cholesteatoma with Acute

Mastoiditis

YAO-LIANG CHEN SHU-HANG NG HO-FAI WONG MUN-CHING WONG YAU-YAU WAI YUNG-LIANG WAN First Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chang Gung University

Deep neck abscess is a rare complication of acute mastoiditis in the era of antibiotics. In preantibiotic era, Bezold’s abscess was the most common cause of the otogenic deep neck abscess. We reported a 19- year-old male with cholesteatoma complicated by acute suppurative mastoiditis, lateral sinus thrombosis, thrombophlebitis of the ipsilateral internal jugular vein and deep neck abscess formation. The pathway of the deep neck abscess formation is different from the classic presentations of Bezold’s abscess. Computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography were complementary for the detailed demonstration of the origin and the extent of the disease. Segmental mural lysis of the infected internal jugular vein was considered to be responsible for the development of deep neck abscess formation.

Key words: mastoiditis; Bezold’s abscess; neck, abscess; sinus, thrombosis

Reprint requests to: Dr. Yao-Liang Chen

Address: First Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

No. 5 Fu Hsing Street, Kwei Shan, Taoyuan 333, Taiwan, R.O.C.

Otitis media is a common disease of childhood. However, it has been estimated that 1.5% of all adults suffered from active chronic otitis media [1]. Complications of otitis media can be categorized into two groups: intracranial and extracranial. Intracranial complications occur in 0.24 % of the patients and include meningitis, encephalitis, brain abscess, epidural abscess and lateral sinus thrombosis. Extracranial complications occur in 0.45% of the patients and include facial nerve paralysis, labyrinthitis, perichondritis, coalescent mastoiditis and subperiosteal abscess [2]. Deep neck abscess is extremely rare in the era of antibiotics. Herein, we present a rare transcranial complication of cholesteatoma and acute mastoiditis with resultant deep neck abscess formation. Imaging studies with different modalities are valuable for tracing the pathway of disease extension.

CASE REPORT

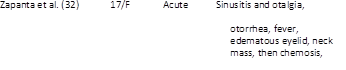

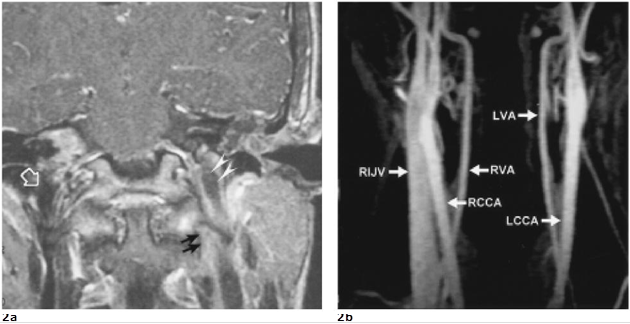

A 19-year-old male came to our emergent unit with pale and ill looking. He suffered from progressive vertigo, vomiting, nystagmus, supervened chillness and fluctuating fever (the spike up to 40.3˚C) for five days. On physical examination, swelling, erythema, heatness and tenderness on his left retroauricular region were noticed. Otoscope displayed perforation of the left tympanic membrane with purulent discharge. Laboratory data showed elevated white blood cell count (23500/mm3) and C-reactive protein (180 mg/dl). Due to the past history of chronic otitis media, he was clinically impressed as acute mastoiditis complicated with Bezold’s abscess formation. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of temporal bone showed soft tissue density filling the left tympanic cavity and cloudiness of the left mastoid air cells with bony erosion at the tympanic tegmen (Figure 1a). Magnetic resonance images (MRI) further displayed swelling of the left temporalis muscle, thrombosis of the sigmoid sinus, jugular bulb and upper internal jugular vein

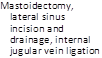

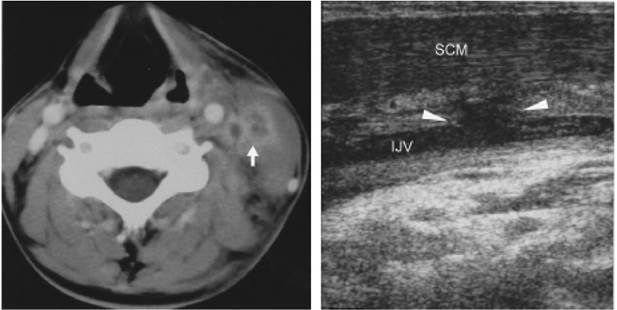

252 Otogenic deep neck abscess

(IJV) (Figure 1b, 2a). T1-based enhanced MR angiogram of the neck confirmed IJV thrombosis (Figure 2b). Enhanced CT of the neck disclosed deep abscess formation that was contiguous to the thrombotic left IJV and deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM)(Figure 3a). High-resolution ultrasonography (HRUS) clearly depicted focal lysis at the wall of the infected left IJV (Figure 3b). The patient underwent left canal-down radical mastoidectomy, tympanoplasty, meatoplasty, incision and drainage of the left neck abscess. Left suppurative mastoiditis complicated by attic cholesteatoma was explored. However, there was no continuation between the mastoiditis and deep neck abscess either by imaging findings or by surgical exploration. Pus culture showed moderate growth of anaerobic bacteria including Peptostreptococcus anaerobius and Peptostreptococcus asaccharolyticus. Treated by thorough open drainage of abscess and intravenous antibiotic administration, the patient was discharged three weeks later with the sequel of left hearing loss (over 100 decibel).

DISCUSSION

Acute mastoiditis can be the complication of preexisting secretory otits media or other chronic disease of middle ear, including cholesteatoma. Before the use of antibiotics it was common and associated in some

instances with serious complications. The mucosa of the tympanic cavity and its extension into the mastoid cells has an inherent ability to overcome acute infection. As a result, acute otitis media and mastoiditis may be self-limited. However, severe suppurative and necrotizing infections of the middle ear can cause systemic reaction [3].

The incidence of complications resulting from suppurative otitis media has significantly decreased in the era of antibiotics. In the beginning of the 20th century, 50% of all cases of otitis media developed coalescent mastoiditis. Recent studies suggested a current incidence of only 0.24% [2]. Complications of otitis media can be grouped into two broad categories: intracranial and extracranial. Intracranial complications include meningitis, encephalitis and lateral sinus thrombosis. Prior to the widespread use of antibiotics, 2.3% of patients with otitis media developed intracranial complications. Nowadays, the rate has fallen nearly 10-fold to 0.24%. The contemporary risk for developing extracranial complications of otitis media is approximately twice of that for intracranial complications, with 0.45% of patients experiencing problems such as facial nerve paralysis, labyrinthitis, perichondritis, coalescent mastoiditis, subperiosteal abscess or Bezold’s abscess [1].

Bezold’s abscess was considered clinically when mastoiditis coexisted with deep neck abscess. In 1908,

|

Figure 1. a. Coronal HRCT shows a focal break-through of the tympanic tegmen (double arrows) indicating the possibility of intracranial complications. b. Axial enhanced T1-weighted MRI displays abnormal enhancement (double arrowheads) in left sigmoid sinus and jugular bulb suggesting lateral sinus thrombosis.

Otogenic deep neck abscess 253

Bezold was the first to describe abscess in the neck arising from mastoiditis. Inflammation and infection may result in necrosis of the mastoid tip, allowing the pus to track from the medial side of the mastoid process through the incisura digastrica (digastric groove). The pus is prevented from reaching the surface by neck musculature, but can track along the fascial planes of the digastic muscle or SCM [1]. Bezold’s abscess usually spreads into the substance of the SCM and confines to the posterior cervical and perivertebral spaces by the pharyngobasilar fascia and the deep layer of deep cervical fascia [4,5]. It may extend into the carotid, prevertebral, danger, and retropharyngeal spaces. By gaining the access into the danger space, an abscess may extend into the mediastinum or into the base of the skull [4]. Due to the depth of their location, Bezold’s abscess may be difficult to be palpated. Pneumatization of the mastoid process leads to thinning of the bone and is considered an important factor in the development of Bezold’s abscess. Therefore, Bezold’s abscesses are more common in adults than in children because well pneumatization of mastoid tip often occurs in adults.

Mastoiditis contributes to most of the lateral (sigmoid) sinus thrombosis. In a series of 22 cases of

lateral sinus thrombosis, 19 were associated with suppurative otitis media and mastoiditis [6]. Suppuration in the middle ear, mastoid, or both may spread to the adjacent intracranial structures through progressive thrombophlebitis, bony erosion, or direct extension, resulting in meningitis, extradural abscess, subdural empyema, focal encephalitis, brain abscess, lateral sinus thrombosis, and otic hydrocephalus. The clinical pictures of lateral sinus thrombosis are well documented: an ill patient with high swinging pyrexia (‘picket fence’ pattern), headache, neck pain and progressive anemia with, less commonly, occipital edema [6].

The occurrence of deep neck abscess and lateral sinus thrombosis may be coincidental, since both are complications of mastoiditis. There is also a possibility that lateral sinus thrombosis may be arisen by retrograde spread from the infected internal jugular vein which had already been involved by Bezold’s abscess. It is however possible that the neck abscesses may be formed by direct regional spread from the infected internal jugular vein that had autolysed [6], as in our case.

Radiological study is indicated in cases of acute mastoiditis or otitis media when there is clinical suggestion of coalescent mastoiditis, which signifies the

|

Figure 2. a. Coronal enhanced T1-weighted MRI depicts thrombosis in the left upper internal jugular vein (IJV). A lowsignal gap and enhanced extramural tissue (double black arrows) imply thrombophlebitis and possibly segmental mural lysis of the left IJV. As compared with the signal void in right IJV(open large arrow), the thrombosis of left IJV shows slight low signal intensity (double white arrowheads) with thick mural enhancement. b. Venous phase of T1-based MR angiogram shows obvious enhanced flow signal in the right IJV but absence of flow signal in the left IJV, confirming left IJV thrombosis. (RIJV: right internal jugular vein, RCCA: right common carotid artery, RVA: right vertebral artery, LCCA: left common carotid artery, LVA: left vertebral artery)

254 Otogenic deep neck abscess

3a 3b

Figure 3. a. Axial enhanced CT displays filling defects in the left IJV and a neighboring abscess (arrow) deep to the SCM. Note increased soft tissue density in the left posterior cervical space due to cellulitis. b. Longitudinal scans of HRUS clearly discloses a segmental mural lysis at the left IJV (arrowheads). Loss of compressibility and low echoic thrmobosis within the IJV are also found.

transition from mucoperiosteal disease to bone disease and even to intracranial complications. CT can show stages of disease progression when infection spreads by way of soft tissue and bone pathways into dural venous sinuses, meninges, labyrinth, facial nerve, epidural and other intracranial spaces [3]. CT is also valuable in early diagnosis of cholesteatoma in the mastoid cavity and exact delineation of abscess formation [5]. MRI is more useful than CT for evaluation of the complications of acute mastoiditis in some aspects. Septic thrombosis of the lateral sinus and jugular bulb is a highly lethal condition. Enhanced CT may reveal evidence of sinus thrombosis, manifested as a filling defect in the vessel (empty delta sign). However, false-positive diagnosis up to 30% of cases has been reported [7]. In contrast, MRI can distinguish between flowing blood and thrombus. Enhanced MRI with gadolinium-DTPA is a valuable adjunct to achieve the diagnosis and to delineate the extent of the pathology [8], whereas magnetic resonance angiography is the procedure of choice for the confirmation of venous thrombosis. CT and MRI can detect concomitant cerebral infection or infarction as well as infection in the epidural or subdural spaces [7].

For jugular vein thrombosis, HRUS can show an intraluminal mass of low or mild amplitude echoes, loss of respiratory rhythmicity and venous pulsation,

absence of venous response to respiratory maneuvers (Valsalva and sniff test) and incompressibility of the thrombotic jugular vein [9]. Because HRUS can depict both transverse and longitudinal planes, it can provide an accurate delineation of luminal compromise by thrombus [10]. For the patient we reported, only HRUS could depict the exact location of segmental autolysis of the jugular wall. Based on the imaging findings of CT, MRI and HRUS, we believe that the deep neck abscess arose from the septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein rather than direct extension of mastoiditis from the mastoid tip, which is the typical pathway of Bezold’s abscess.

Early surgery is mandatory to treat severe mastoiditis such as coalescent mastoiditis and subperiosteal abscess. The infected neck or abscess formation needs thorough drainage. Given the low incidence and lack of consistent signs and symptoms, Spiegel et al suggested contemporary practitioner must be rely on radiological images to determine the presence and pathway of mastoid abscess [1].

REFERENCE

1. Spiegel JH, Lustig LR, Lee KC, Murr AH, Schindler RA. Contemporary presentation and management of a spectrum of mastoid abscesses. Laryngoscope 1998;108: 822-828

2. Kangsanarak K, Fooanant S, Ruckphaopunt K, Navacharoen N, Teotrakul S. Extracranial and intracranial complications of suppurative otitis media. Report of 102 cases. J Laryngol Otol 1993; 107: 999-1004

3. Mafee MF, Singleton EL, Valvassori GE, Espinosa GA, Kumar A, Aimi K. Acute otomastoiditis and its complications: role of CT. Radiology 1985; 155: 391-397

4. Gaffney RJ, O’Dwyer TP, Maguire AJ. Bezold’s abscess. J Laryngol Otol 1991; 105: 765-766

5. Smouha EE, Levenson MJ, Anand VK. Parisier SC. Modern presentations of Bezold’s abscess. Arch Otolaryngol 1989; 115: 1126-1129

6. Pearson CR, Riden DK, Garth RJ, Thomas MR. Two cases of lateral sinus thrombosis presenting with extracranial head and neck abscesses. J Laryngol Otol

1994; 108: 779-782

7. Bleck TP, Greenlee JE. Suppurative intracranial phlebitis. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Mandell: Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 5th ed. Philadelphia, London, Toronto, Montreal, Sydney, Tokyo, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000: 1035

8. Fritsch MH, Miyamoto RT, Wood TL, Sigmoid sinus thrombosis diagnosis by contrasted MRI scanning. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1990; 103: 451-456

9. Gaitini D, Kaftori JK, Pery M, Engel A. High-resolution real-time ultrasonography. Diagnosis and follow-up of jugular and subclavian vein thrombosis. J Ultrasound Med 1988; 7: 621-627

10. Wing V, Scheible W. Sonography of jugular vein thrombosis. AJR 1983; 140: 333-336